I’ve long been interested in the popular geography of Great Britain, but also annoyed by the continual government reorganisation that seeks to confuse it. The passing of the Local Government Act of 1888 established county councils (or ‘administrative counties’) based upon the boundaries of existing historic Counties in England and Wales, but subsequent legislation has been far more destructive.

My interest in this topic is no doubt driven by my desire to organise everything, but it’s worth noting that I grew up in Horley, a town that campaigned hard to remain within Surrey when the Local Government Act of 1972 sought to have it join neighbouring West Sussex.

This act was particularly far-reaching. Not only did it create new ‘metropolitan counties’ around the six major conurbations of England, and adjust the boundaries of remaining ‘non-metropolitan counties’, it also introduced several invented county names such as ‘West Midlands’, ‘Merseyside’, ‘Cleveland’ and ‘Avon’.

Luckily for Horley, the passing of a subsequent act meant it remained in Surrey, but for the rest of England and Wales, it’s geography had now become subject to political whims, no longer fixed or predictable.

In recent years, legislation has focused on the transfer of administrative functions from county level authorities to smaller administrate districts. For example, legislation passed in 1985 abolished the six metropolitan counties and passed much of their function to the individual boroughs. The present government favours the creation of one-tier ‘unitary authorities’ that work in a similar way. In short, the concept of a county as an administrative district is disappearing, suggesting that the redrawing of their boundaries was largely pointless.

Counties are important – not only useful for way-finding, but as entities to affix local identities and cultures to, and help tell the story of Britain. Yet their continual reorganisation has left people confused as to their function, names and location.

Psychoville

Such confusion was evident when I sat down to watch Psychoville last Friday. The first episode of this new dark-comedy series focused on letters being sent to five characters around the country, but it was striking how each location was referred to using these different understandings of a county.

Salford, Manchester

The first location named was technically wrong (but no doubt commonly used) in that it should have read ‘Salford, Greater Manchester’. Had it used an historic County, this would have been ‘Salford, Lancashire’.

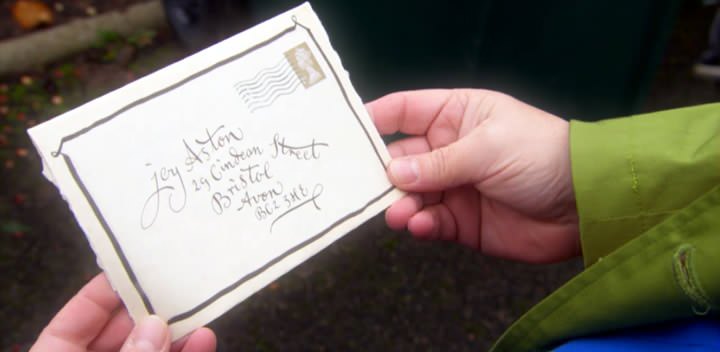

Bristol, Avon

This graphic is perhaps the best example as to why we should return to using historic Counties in addresses given that Avon no longer exists! Created as part of the 1972 reorganisation, it was abolished in 1996 and replaced with four unitary authorities, three of which returned to their ‘ceremonial counties’ of Somerset and Gloucestershire (whilst Bristol became a ceremonial county in its own right).

Using an historic County would have resulted in the location referred to as ‘Bristol, Gloucestershire’.

Ilkley, Yorkshire

The third location given is actually shown on-screen using an historic County, but if you watch closely you will see the actual letter has the address written down as North Yorkshire – an unfortunate error as Ilkley is in the West Riding.

Eastbourne, Sussex

This location was also referenced using a historic county, with Sussex displayed instead of the current ceremonial county of East Sussex. I suspect this may have been due to the space available on screen.

Wood Green, London

Formally Wood Green was a municipal borough within the county of Middlesex, but is now part of the London Borough of Haringey, one of 32 London boroughs within Greater London. This is a bit of an anomaly, as Greater London is formerly classed as an ‘administrative area’ and ‘local government region’, but not a county.

Whilst Greater London assumed parts of neighbouring counties and lead to Middlesex being abolished entirely, this historic county still exists in the public consciousness. A tin of Heinz Baked Beans will show the company address as Hayes, Middlesex, whilst a can of Coke may list an address of Uxbridge, Middlesex.

Using historic Counties for addresses in London can be confusing, so the recommended form is to use the County followed by the Post Town, for example:

Wood Green

Middlesex

LONDON

Further Information

A whole host of information on this topic is available from the Association of British Counties, an organisation that is seeking to re-establish the use of historic Counties as the standard popular geographical reference frame of Britain. I’ve already taken them up on their advice of using historic Counties in addresses, and I’m sure membership will follow.