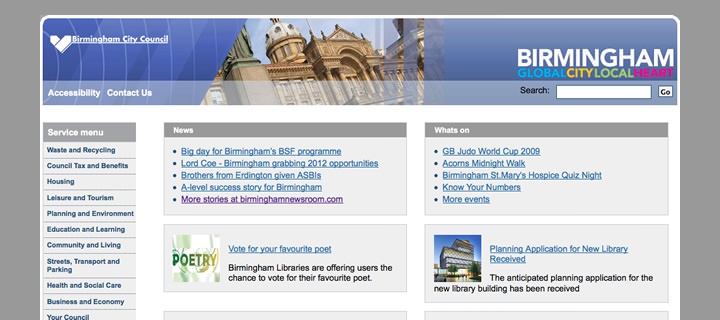

Last week Birmingham City Council launched its new �2.8m website. Delayed, over budget and woefully inadequate, it rightly faced a storm of criticism on Twitter and from the local press.

Whether as a result of the public service dating game (the council choosing the outsourcing firm Capita rather than a specialist web design agency), or the single success criteria being a site better than the one it replaced (a low baseline), the whole affair only succeeded in demonstrating how not to handle a large scale web project.

Jake Grimley, managing director of Birmingham based Made Media, summed up perfectly why many of us in the industry and with connections to the city, felt so let down:

It’s not really the lack of RSS Feeds (inexplicable as that is) or the failure of the CSS to validate, or the difficulties keeping the site up on its launch day that really bother me. It’s the complete lack of attention to detail or quality in the content, design and information architecture that I find astounding. It’s the equivalent of re-opening the Town Hall with bits of plaster falling off, missing roof-tiles, and sign-posts to facilities that never got built.

Given the involvement of Capita (often referred to as ‘Crapita’ by Private Eye), we were probably wrong to expect anything more, yet the council’s response to this well-placed criticism only served to make a bad situation worse. Glyn Evans, director of ‘Business Transformation’ was quoted as saying:

We have tried to design a site suitable for the majority of our residents. We are not designing it for the Twitterati

Not only did this comment fail to recognise that those disappointed users on Twitter were likely the very same residents and business owners who were using the site, it’s even more striking given Birmingham’s aim to become the digital media capital of Britain.

Walsall Gets It Right

Yet the relationship between a council and it’s residents online needn’t be so strained. This controversy reminded me of the different approach taken by my former local authority, Walsall Council, who unlike Birmingham City Council has successfully embraced Twitter to connect with it’s citizens.

Let me give an example. Earlier this year I wrote about their logo, and asked for information about who was responsible for its design, yet this yielded no response. However, on discovering the @WalsallCouncil account, I asked the same question, and not only did I get an answer, but members of their Print and Design Unit and Press Office commented on my post, giving me more information than I ever could have hoped for.

Walsall Council replying to a question from me on Twitter.

Yet aside from answering questions about a logo, their presence on Twitter is providing a real service to the community. Be it suggesting activities for families over the summer break, allowing users to report problems such as fly tipping or pot holes – or simply by featuring images of the area taken by local photographers – this is very much a two-way communication channel.

Having experienced this ability to engage directly with such an organisation, it is clear that the future success of local government lies with authorities being willing to use social media tools to better converse with their residents. One can only hope that Birmingham City Council will come to realise this sooner rather than later.