Earlier this month I spent a week volunteering at the XX Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

Any conversation regarding these Games often involves comparisons to the Olympic Games held in London two years ago; a tough act to follow given their prestige and success. Organisers in Glasgow were keen to point out that their games offered a different spectacle – a 11 day festival of sport and culture designed to promote goodwill between the 71 nations and territories that make up the Commonwealth – and should be judged on that basis alone. But with a number of popular athletes unable (or unwilling) to compete, questions were raised about the validity of this multi-sport event, which many consider an anachronism.

Still, a competition not featuring athletes from America, Russia and China has its upsides: it allows smaller nations a chance to shine and can showcase a new generation of athletes. It’s also an opportunity for British athletes to compete for their home nations, a fact made more interesting given the upcoming referendum on Scottish independence.

Discovering Glasgow

From the perspective of a volunteer, comparisons are possibly more valid. The success of the Games Makers in London accounted for an unprecedented number of people (over 50,000) applying to be Clyde-siders in Glasgow – more than the last two editions of the Commonwealth Games put together.

For me, volunteering a second time was an opportunity to recapture the magic I felt two years ago. It also meant spending time in a city I’d visited briefly just once before.

Following a successful application interview, I spent a further three weekends in Glasgow for orientation and training events. I enjoyed exploring this vibrant and engaging city and admiring its abundance of stunning architecture. The River Clyde crossed by iconic bridges and framed by oddly shaped buildings. Shopping districts featuring exquisite Victorian shopping malls and department stores. The sometimes brutal landscape the result of driving the M8 motorway straight through the heart of the city in the 1960s.

The recently completed Anderston pedestrian footbridge (in the background of this photo) sits among a number ‘bridges to nowhere’ that can be found around the M8.

Hearing Hampden Roar

In January I found out that I would be based at Hampden Park, where Scotland’s national football stadium was being converted into a temporary athletics track. The ingenious method used, in which over 6000 structural steel stilts were used to build a platform 1.9 metres above ground, inspired the slogan for the volunteers who would be working there: ‘raising the games’.

As a last mile team member in London, my role was limited to greeting spectators outside the Olympic park. In Glasgow, Clyde-siders within the spectator services team could find themselves doing many different tasks; ticket taking, ushering people to their seats, monitoring access points or even driving the accessible buggies.

I failed to get a role inside the stadium, but working outside, where I could interact more fully with the crowds, was a fine alternative. I felt none of the nerves or awkwardness I did during my first few shifts in Stratford. In fact, I felt surprising comfortable joking with crowds, high five-ing with kids (and adults) and cheekily grabbing the odd chip!

That said, I’m not sure the atmosphere outside the venue matched that seen in London. While the weather was undoubtedly a factor – a policeman joked that you knew it was summer in Glasgow because the rain was warm – converting an existing venue rather than designing one from scratch led to a few uncomfortable compromises. The perimeter fence erected around the stadium complex had a single point of entry for the public, reached from the train station by means of a 15-minute walk over a large hill. This was to the displeasure of many, especially on the first Sunday when queues grew quite long.

However, as I discovered when I attended the athletics as a spectator, nothing could match the atmosphere inside the stadium. I doubt the famous ‘Hampden roar’ has been louder or more intense. This was certainly true when Scottish athletes were competing, but when England’s Greg Rutherford won gold in the long jump, there wasn’t a single person not jumping and shouting for joy.

The Clyde-sider Experience

Each shift began inside the stadium with everyone taking part in a haka (minus the dancing), before being dispatched to larger area groups. These groups were subdivided into smaller sub-teams, who were then briefed by their team leaders. A debrief at the end of the shift allowed us to relay any problems and suggest how things could be improved the next day.

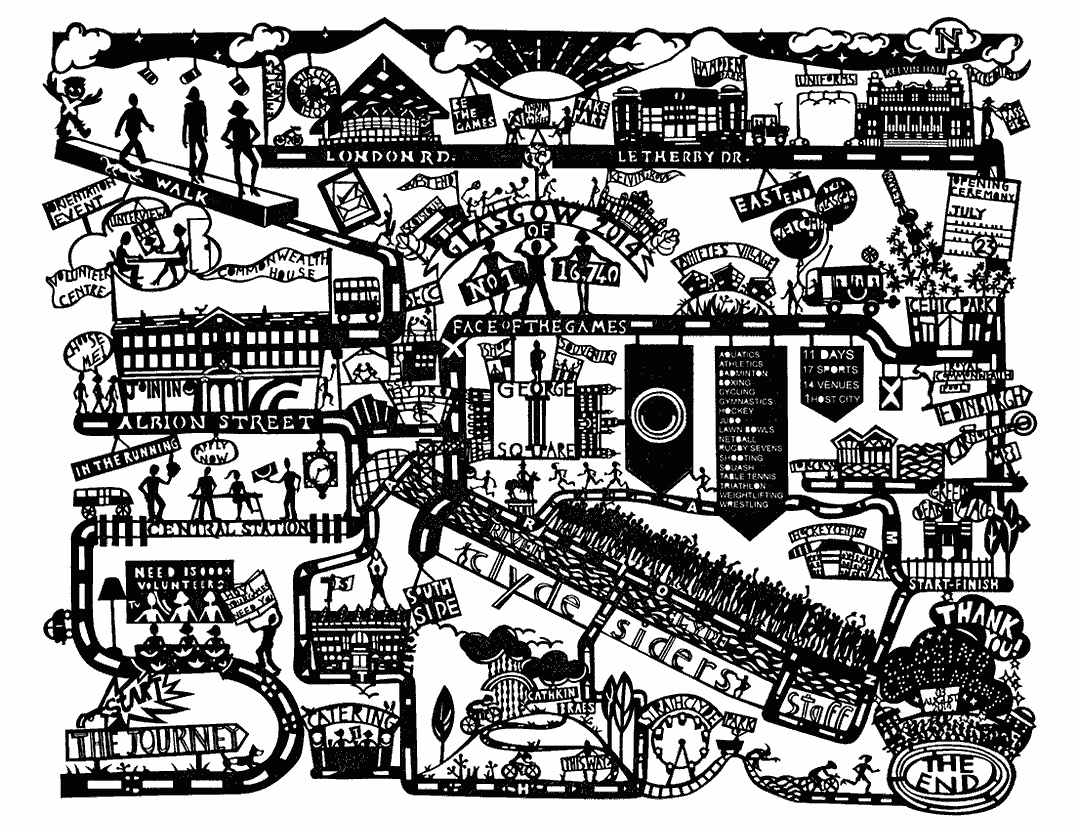

Illustration by Christine J Thomson.

The organisers went to great lengths to ensure Clyde-siders were looked after and appreciated. Between ingress and egress, volunteers were able to sit in the stadium and watch the action. The sandwiches available during lunch breaks were a particular highlight, with hot items available during evening shifts. Volunteers were also given limited edition gifts, including a beautiful commemorative print celebrating the journey Clyde-siders had been on and shown above. The uniform, while less distinctive (read: less embarrassing) than those worn in London was more rugged, and clearly designed with Glasgow’s weather in mind.

A Reminder

The best feature of the uniform was that it gave people a reason to start a conversion. I spoke with a number of Glaswegians who were immensely proud of their city, slightly embarrassed by the opening ceremony, and thankful for those who offered to volunteer.

While no event could hope to compete with the Olympic Games, in terms of volunteering, Glasgow 2014 was arguably better than London 2012. I suspect this was due the smaller team working at Hampden, and thus recognising fellow colleagues more quickly. But with only six shifts, the point at which I was getting to know everyone, it was time to say goodbye.

Still, making comparisons to London seems foolhardy, although that experience did allow me to enjoy this one more fully. I was also reminded why I wished to reprise this role in the first place: interacting with the public, every smile was validation that, no matter how small my contribution, I was making a difference.